Do I first tell you about recording tools, both hardware and software, digging into explanations of what various tools can do for you? Do I start with lessons in simplicity, just to help a beginner get started? Do I give you examples of different approaches to recording? I intend to do all these, to the limits of my knowledge and ability (limits all too quickly met, which is why I’m always soliciting contributors), but not today.

Today I’m going to give you a brief introduction of some of the tools and techniques I’ve tried over the years, a few words about the process itself, and several examples of the results. Brief, of course, is a relative term.

This story starts out as a comedy, of the obnoxious, half-hysterical sort, of someone who’s both clueless and irritatingly eager to get at an elusive goal…it’s cute if it’s your wiz-kid nephew out in the backyard building rocket ships but in an adult it comes off more like an outtake from Dumb and Dumber. (Yes, I’m talking about how I started recording.) Now days it’s easier to break into the process of recording your poetry, modifying it and turning it into some sort of temporal, 4-dimensional, audio composition. All you need is a computer, which almost everyone has, some freeware, and a way to connect a microphone to the computer (if the computer has a mic, that’s it). (Actually, you can do this entirely with hardware on a portable recorder or a portable studio, though you’ll still want to transfer to a computer and/or the internet.)

= = = = = = =

In the 1980s, into the 1990s, I kept trying to record readings of my poems, ambient sounds, my older daughter’s infantile squawks, but I was always held back by poor technology, poverty, and ignorance of the available tools; and, ultimately, I had no way to combine the various recordings into an actual composition. My ideas were not focused as to what I wanted to do and my unsubtle hints to musician friends about collaborating gave them just one more reason to keep their distance. These recordings were all done on cheap portable stereo cassette players or similarly cheap component cassette players (part of a stereo system, if you’ve come of age on earbuds), with the aid of a really cheap Radio Shack mic.

By 1995 my ideas were becoming a little more tangible and seriously too weird for any of the musicians I knew. A couple of friends, with a semi-pro home recording set-up in their attic, had begun telling me that what I needed was a 4-track. I’d heard of 4-track recording: Sgt. Pepper’s was done on 4-track at Abbey Road. You need a reel-to-reel recorder that costs tens of thousands of dollars combined with a mixing console and microphones and who knows what else. After months of this disheartening advice, my look of utter confusion caused them to finally pull me aside and show me a mail order catalog for musicians: 4-track cassette portable studio for about $400, a recorder with a built-in mixer—musicians had been using them for years. To get started the only other thing I’d need is a microphone. I ordered a Fostex XR-5 in March 1996 and my friends loaned me an Audio-Technica Pro25 microphone, designed for use with bass amps and kick drums (loud and low-pitched sounds…a Shure SM-57 would have been a better choice, costing not much more than what I eventually paid for the borrowed mic, but I’d never heard of it).

If I had been a musician that would have been all I needed. Off the bat you have four tracks of sound: one for the poem; one for banging on something; and two more for other sounds. If that isn’t enough you can bounce tracks: for instance, record something onto the first three tracks then play all three as they’re recorded to the fourth track; record two more tracks and bounce them to the third—you can get a pretty complex arrangement this way (or, in my case, a very cluttered one). Better yet, you can do weird and creative things by varying tape speed or flipping the tape to record something backwards. The process is quick and spontaneous, just plug in a microphone, flip a few switches, turn a few knobs, and make noise (oh yes, and press record). You do have to pay attention to where the cables are connected and make sure those switches and knobs to direct and monitor your signal go the right way, but, really, it’s quick, easy, and a lot of fun to work this way (there are now digital portable studios that afford roughly the same process, or if you keep your computer’s set up simple it remains fun—so, yes, I feel nostalgia and sometimes forget how much I hate everything tape based).…The main drawback is in terms of quality: cassettes never had a great sound to start with; when you bounce tracks the noise, such as tape hiss and circuit noise from your equipment, accumulates.

Fostex XR-5 cassette 4-track portable studio.

Not only am I not a musician, especially lacking in rhythmic skills, I had grand ideas of almost symphonic creations made of household sounds. Within two weeks I had ordered a Roland MC-50 Mark II sequencer for controlling the playback of sounds and a Roland MS-1 phrase sampler for recording around and outside the house. Probably the simplest analogy to a sequencer is a word processor: like a word processor a sequencer records basic messages like note on, note number (each note of a traditional keyboard is assigned a number), note velocity (how hard a piano key was struck)—rather than the letters and numbers of a QWERTY keyboard—which when played back communicates these messages to other devices, such as hardware or software synthesizers or samplers, what to play (as in a word processor, it gives you the letters of the alphabet without telling you the formatting such as font, color, or text size, so you could have your playback sound be from any instrument, familiar or something totally original). In other words, I was introduced to the nightmare known as MIDI. Sequencers are still alive and well in hardware in the form of the AKAI MPC and many musicians prefer to compose with them rather than having to deal with a computer (newer hardware/software hybrids such as Native Instruments’ Maschine maintain the feel of a hardware sampler while utilizing the storage capacity of a computer’s hard drive). But sequencers are also an essential feature of almost all modern Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs), if your computer is connected to a piano-like MIDI controller (or a drum controller, wind controller, or even a paper controller (I don’t want to get into that, just heard about it a couple days ago). Actually, you don’t need a hardware controller: MIDI can be created entirely within the DAW, either by drawing in the notes or by step recording (either way, a very tedious process).…The sampler was a tool for recording real world sounds. At the time there were two main types of sampler. The one kind was made for creating or simulating instruments and most software samplers (such as NI’s Kontakt), as well as many hardware models and wave based synths are of this sort: very few of which give you the power to record your own sounds though most will allow you to create your own instruments once your sounds have been uploaded (ever wanted to do a simple melody of sneezes?). Originally phrase samplers, such as the AKAI MPC, were used to construct songs from samples of other people’s music (think of classic hip hop recordings by Public Enemy, Beastie Boys, Jungle Brothers, or club favorites like Fatboy Slim—though I don’t know if any of them actually used an AKAI). I chose the Roland, though it would only hold 28 seconds of sound, up to 32 samples (unless you could afford a memory card), because I could plug in that inappropriate microphone (for bass amps and kick drums) and take it with me anywhere to record any sound, edit the sounds within the sampler, and use it as a playback instrument.

So I now had some element of field recording and the option to construct with any sound. This is still at the heart of my audio compositions, with or without poetry.

(The way I started working, after purchasing these electronic instruments and controllers, was to maximize the number of sounds input while recording any given track. This is a form of pre-mixing and can lead to many retakes and headaches if you don’t get the levels just right.…First, I’d record time code to track 4, from the sequencer. Then I’d record track 1: almost always the sampler with a basic rhythm of my home recorded sounds; usually a keyboard for instrument sounds, in this case bass if I was using any; then up to two microphones, one for additional live tracking of banging on things and the second for voice recording. Then I’d do roughly the same thing to tracks 2 and 3, with more samples, synths, and live tracking. On the finished mix track 1 would be panned center, which is why I put any bass and the primary rhythm there, while tracks 2 and 3 would be panned extreme left and right. Finally, I’d make it uneditable by recording my voice over the time code on track 4.…My method was similar when I switched to a digital 8-track recorder (see below), but more relaxed. The primary advantage was that I could go back to bouncing tracks because there is so little accumulation of noise, compared to the cassette 4-track. Typically, I’d record samples to the first six tracks, still using the sequencer and sampler, then bounce them to tracks 7 and 8. This is another form of pre-mixing. Compared to the 4-track, on digital I would never really have to start all over again if something didn’t balance well with the other sounds. I could just remix another bounce (the VS-880 has eight virtual tracks, so, if I’d wanted to, I could have tried eight mixes of tracks 1-6 before I’d have to actually re-record anything), or re-record a single bad track if that was the problem. (Another plus is that I was never wasting an audio track to record time code. A whole different part of the VS-880 would take care of that.) Then I’d add tracks of MIDI-controlled synth or realtime recordings of noises and voice. At that time I made much more use of my Stratocaster than I do now.

This track, “Night”, is one I recorded to 4-track, circa 1997. It’s simpler than most in that there’s nothing to it but my own samples, one of which was looped, and voice. (The samples listed include: a wooden whistle, like a very small recorder, distorted; the side of my desk; the plastic wrapper of a roll of duct tape struck with a butter knife; clacking plastic spoons; a comb; slinkies; a mailing tube and rolled newspaper; a cassette case; a Bestine can, distorted. The Bestine can, playing the part of a snare drum, is an example of how a sound can be distorted with just the formant feature of the Boss VT-1 (see below). I think that’s also what I did with the wooden whistle, which sounds almost like a night bird.) The samples were mainly recorded as a few random MIDI performances (I do a lot of random), then replayed by the sequencer and sampler as it was recorded to tape. Followed by my reading of a poem, obliterating the time code on track 4.)

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/night-draft-1-2a

Roland MC-50 Mk II Micro Composer, circa 1996. It doesn’t look very musical or inspiring does it. There’s nothing spontaneous or innate about working with such a tool.

Roland MS-1 phrase sampler. Portable recording and instrument. The buttons on the lower right, numbered 1-8, are performance pads, played by pressing or tapping. They could play back the whole sample, such as a percussion hit; play back an extended drone if set to loop within the sample; repeat a phrase, such as a drum pattern, if set to loop the whole sample; or create chopped and stuttering effects if set to play as long as you’re pressing the pad.

Of course I bought other things to embellish my creative possibilities: a multi-effects processor for reverbs and delays; a compressor (never learned to use it and hated the noise it generated); a better MIDI keyboard; other microphones; an electric guitar; as well as a ton of cables and adapters and other esoteric devices that the studio world seems to flaunt. After a year of working with MIDI and cassette I grew frustrated by the difficulties of synchronizing them, plus I wanted more tracks of recording, and bought a Roland VS-880 digital 8-track recorder (a digital portable studio). As an object I still look at it with a very twisted esthetic longing. I came to hate using it because of the difficulties of back up and retrieval and because I became obsessed with cleanliness of sound…good sound is nice to have but, really, ultimately, the only things that matter are the performance and how the pieces fit together (that is, the composition).

The one tool I’d like to mention, something not standard in most recording environments, that I’ve used over the years, is the Boss VT-1 voice transformer. Originally created for DJs, it’s obviously great for gimmicks like robot voices and chipmunks but can also be used for creative effects, and not just on voice. With it you can control pitch, for the standard giant and munchkin voices, but also formant, which is where it steps into the world of serious sound design. Basically it mimics changes in the apparent size of your vocal cavity (this can be very interesting when you apply it to things like guitars, changing only the formant but not the pitch). With it you can make somewhat believable transformations of age and gender, as well as more subtle changes to your regular voice.

Boss VT-1 voice transformer. By eliminating pitch you create a basic robot voice. By changing only the pitch you can create generic giant and chipmunk sounds, as you can with changes in tape speed. Changing just the formant can be very interesting when used with voice or any other sound. Making small changes to both pitch and formant is how you come closest to authentic seeming changes of size and gender.

This is one of my more recent excursions into voice transformations, Hello Earth, where I did an ad lib as our planet’s mother.

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/hello_earth

The one piece of equipment I lacked in those days, and one I cannot stress strongly enough for its importance, is a pre-amp. If you’ve taken a step beyond recording with your computer’s built-in mic or using some sort of USB microphone and are using a hardware audio interface, or if you’re using some sort of portable studio, I really recommend a pre-amp for your microphone—there’s more to it than phantom power. With that 4-track analog and 8-track digital, it would have made a huge difference by making the primary signal (my voice or an instrument) louder and clearer while keeping the circuit noise of all the electronics to a minimum. Even with a hardware interface it’s nice to use a tube pre-amp to color the sound a little. If you’re going for a clean sound the pre-amp colors it just a little. If you want distortion this is still considered the most desired form of noise: that is, tube distortion. It would have been a very cheap piece of gear ($100-$200) for something that would have been a great asset to my signal chain. Pre-amps are not glamorous like a signal processor, they don’t make obvious changes to your sound the way a reverb unit or delay unit can, but I wish I’d gotten one before I wasted money on all those other tools and toys. (Since shifting to computer to record, I’ve owned a Belari MP-105 and a Presonus Blue Tube. The Belari never sounded right to me, too blatant, too simple. It seems the Blue Tube is not as popular for exactly the reason I like it: it’s too clean, going from an almost transparent sound to a subtle fuzz of distortion.)

= = = = = = =

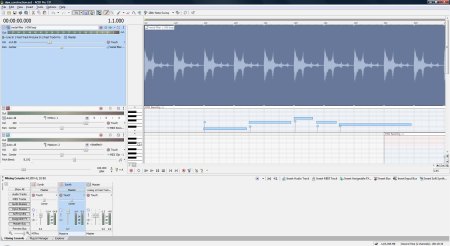

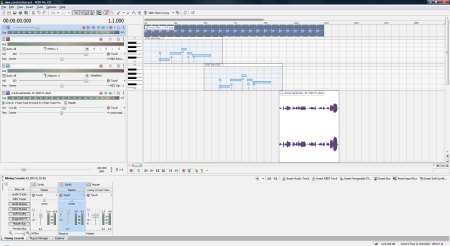

My way of working within the box, within the computer, has gone through two major periods: one running from roughly 2003-2006, almost entirely with commercial loops, and the second beginning in 2009, as I return to something of the strangeness and spontaneity of my earlier recording methods.

I don’t remember when I bought my first computer, maybe 1999 or 2000. The operating system was Windows 98 SE.…Editing my poems had been such a hassle in the old days (circa 1987 and earlier), either rewriting the whole thing by hand or, worse, retyping it: that and other reasons caused me to give up on the written word (falling in love might inspire poetry but being in love, living the life, making a home and all that, left me speechless; so did having a full time day job for the first time in my life). Then, circa 1992, I discovered and bought a word processor. Out came a torrent of words, many attempting to be politically correct while still venting spleen (a most unnatural combination).…When the word processor died and I went to look for another I found that they’d been taken off the market because computers had become so popular, cheap, and versatile. I did not want to buy a computer.

Learning to record had caused me to set aside most of my drawing. Learning to use a computer also led me to set aside recording as I spent a couple years cataloging my art (typing hundreds of poems and rants, scanning thousands of drawings and paintings).…Very slowly I started to use the computer for audio, first by converting some of my LPs to CD-R. This began by experimenting with a bootleg of Sonic Foundry’s Sound Forge (now owned by Sony). This was also my introduction to Audacity, before I bought a legal copy of Sound Forge and learned to use their noise reduction software.

Up until the autumn of 2001 I’d been making a living as a screen printer. Once the economy crashed and I was unemployed, an overly generous cousin gave me a couple hundred dollars to help my finances: I’m sure to her I misused the money when I purchased Sonic Foundry’s ACID Pro (version 3, I think) (also now owned by Sony), but it was the one thing I did in that nine months of joblessness that has had a permanent impact on my life.

As it is, I’m the kind of person who spends days reading the manual before plugging in a new device (seriously, when I bought that Fostex in 1996 I really did wait two days before plugging it in), but this computer thing took me longer. I don’t think I did much with ACID for over a year (by then I had a new job in a new field—installing office furniture).

(A brief digression regarding DAWs. I think the earliest programs were strictly MIDI. If you had enough sound modules, with or without a built-in keyboard, you could construct a large multitimbral composition to be played back like a symphony of player pianos. Of course it took a lot of programming and the computers crashed with even such light usage programs. As an independent medium MIDI has never caught on.…Part of why Pro Tools became a studio standard is that it was one of the first programs for the recording of live sound on a computer, basically replacing tape based recording formats (both analog and digital—the 1990s being the era of the ADAT). Pro Tools was a very spendy proposition and has remained so until recently, requiring expensive interfaces and converters for the sound coming and going from the computer.…The buzz in the 1990s was looping, as on the aforementioned AKAI MPC. ACID was the first program to make this ridiculously easy within the computer. Now, of course, pretty much all DAWs do all three, allowing you to work with MIDI, track live performances, and construct with loops. Usually, both hardware and software are extremely easy to set up; then it’s just a matter of doing what you really wanted to do in the first place: compose.)

For several years my compositions on the computer, within ACID, as I learned my way within the program and as the program evolved, were almost entirely made of canned loops from the ACID loop library. Instead of wandering around the house banging on things or just hauling strange objects to my room to record, I’d spend hours exploring my hard drive to find sounds that would work together. I have to liken this to the process of digging through old magazines and illustrated books to find images for a collage (almost exactly what someone is doing by creating loops from old records).…At it’s best, I view the use of loops as the poor man’s way of hiring a studio musician. Because you’re poor you can’t actually tell them what to play, you just have to accept whatever they’re in the mood to do for you that day. I’ve never been comfortable with the process, not because I think it’s in some way lazy or cheating, tapping into someone else’s creativity, not even because if hundreds or thousands of people are using the same loops everything will sound the same (I don’t think there’s much out there that sounds like what I’m doing). No, I dislike using commercial loops because they’re too professional, too pretty, and too musical.

This is one of my more satisfying recordings done with loops. It ties in well with “Night”: this is “Insects”, circa 2003.

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/insects-draft-1-4a

It took me so long to get comfortable with working on the computer that I continued to record my voice to the VS-880, then transfer it to the computer, recording it to Sound Forge. After spending hours, more often days, building up the “music” in ACID, I’d have the rhythm memorized, so when I’d record the reading of the poem the performance would be almost completely synchronized to the composition (needing a little tweaking) and attuned to the feel of the sounds. (Even at the beginning I’d tend to create an instrumental, then find an existing poem or write something new that matched the feel of the piece. I almost never do something that could be construed as illustration, that is composing sounds that amplify the meaning of the text.)

2006…I was tired of working with loops. My job was wearing me out. What else was going on? Not sure, but I started to loose interest in audio compositions. Started to loose interest in a lot of things. I did a collaboration with Charles Schlee, worked on a couple other things in 2007, then my computer died in July, 2008. This was roughly two years of computer hell: the first year because almost none of my audio software or hardware was compatible with Vista 64-bit; the second year because Native Instruments was continuing to turn away from 64-bit until the release of Komplete 7 (I don’t mean to pick on them, this denial was industry-wide). I almost ditched ACID because of it. I did have to switch from an M-Audio Firewire Solo, because they did not have a compatible driver, to a Focusrite Saffire audio interface (and even that gave me trouble at first).

The result of a two-year headache? Almost totally altering the way I work, returning to greater usage of original samples, the usage of field recording, more live tracking, and performed rather than sequenced MIDI instrumentation. I started recording directly into ACID, so my readings and other performances are in real time and more directly attuned to the sounds (quite a few more ad libs in recent years, as in “Hello Earth”, above). Even though I’d had NI’s Komplete on my computer for years (bought Komplete 3 on sale just before Komplete 4 was released—August 2006—and some of their keyboards came with a version of ACID earlier that year or in 2005) I’d hardly ever used any of their magnificent instruments. I still haven’t dug very deeply though almost every composition of the past couple years features several of their synths and samplers. (For the past year or more I’ve been playing with one of their obsolete processors, Spektral Delay, to create mutating drones.) The essential change is that what I do now is play more often than work. I still waste a lot of time browsing synth patches rather than loops and spend many hours tweaking both the MIDI data and the settings for each individual track’s effects and levels, but, really, it’s again become fun to record audio. (Also, it’s been more fun since I subscribed to soundcloud.com. I don’t have a large audience but just knowing that a few people will hear what I’ve created is a great feeling.)

The other major change, in 2011, was the purchase of a portable recording device (a Zoom H-1). When I began recording in 1996 the cheapest portable devices were Sony DAT recorders (with moving parts to break down…even worse, if I remember correctly, they were consumer grade and had copy protection that would interfere with transferring to other digital devices), I think starting at $1300 dollars, plus the purchase of microphones. The H-1 sells for about $100, is a complete recording tool with built-in microphones, stores hours of high quality audio while running on two AA batteries, and needs nothing but a USB cable to import your recordings to a computer (not absolutely necessary, because you could transfer the data by inserting the micro-SD card into your computer, but the accessory pack comes in very handy with a tiny tripod, foam windscreen, and USB cable).

I’d like to end this with something out of context for a poetry blog. First is a composition based on a processed field recording, “You Are Welcome”, that is also a vocal ad lib. The primary sound source is a recording of snow pellets falling onto dried leaves. It was processed numerous times within Spektral Delay. There is some additional instrumentation and a drum loop. (For a “purer” presentation, listen to “The Angels Are Agitated“.)…Following this is a synth instrumental, featuring presets from Native Instruments’ Absynth, Massive, and FM8. It is a multitrack recorded MIDI performance called “Sunday Morning”.

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/you-are-welcome-draft-1

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/sunday_morning