Just because you’re an intelligent and creative person (that is, a poet) doesn’t mean you know anything about recording or composing, or that you know anything about the technology for creating any kind of audio composition. This is specialized knowledge with a specialized language and specialized tools: it takes a while to learn it, even the basics.

I’m going to take a few minutes to introduce you to some of the most rudimentary means of construction within the recording technology accessible to almost anyone in the modern world: the DAW, or digital audio workstation, on a computer. That is, I want to introduce you to recording actual sounds, creating with MIDI, and looping.

I do my sound editing and some basic recording in a program called Sound Forge, then construct an audio collage in ACID Pro. (These are moderately expensive programs, both of which come in much cheaper versions. I’ve been spoiled by good software and it is now one of the few luxuries in my life. Almost all the DAWs have at least one limited use version at a lower price, and almost all also have a version that is free. The wikipedia article on DAWs lists quite a few options, both paid and free.) In the late 1990s there were huge differences in what each program could do. For instance, most of the programs were nothing more than MIDI editors and controllers. Pro Tools made its mark by being a dedicated recording platform—turning your computer into a digital tape deck. ACID was unique as a loop production program. Now they all do pretty much the same thing.

Twenty years ago loops were the buzz, very mysterious and very intimidating (at least to traditional musicians). All there is to a loop is a sound recording set to continuous playback (yes, that annoying theme song that keeps playing while a DVD is in menu mode is a loop). Looping in performance—that is, performing and recording a musical phrase and setting it to repeat, then creating more layers the same way—takes talent and timing. The subject here is a bit more static and slow moving. The loops I use are created by setting the beats per minute (BPM) by selecting how many beats a recording has or by selecting a tempo (say, 110 BPM) in an audio editing program like Sound Forge (this is also known as acidizing). You can buy commercial loops, such as short passages of drumming, that are ready to go, and I’ve used them but find the process dissatisfying. Most often I create something original made from recording found and household objects abused in various ways.

In 2003 I found some furnace filters while cleaning out a commercial space, on my day job, and brought them home to rub and bang on. The following recorded clip is one of the results:

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/metal-filter-1-098-loop/s-b5TT8

By looping it and placing it on the timeline in ACID I’ve created a crude rhythm. You’ll notice that the sound is quite different now: that’s because the tempo of the sample was set to something like 298 BPM but the composition is at 110 BPM. This stretches the sample beyond its limits, creating artifacts very much like zooming in too far on a photo. It’s sort of like an audio pixilation.

Here is how it sounds:

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/deformed-loop/s-EotVU

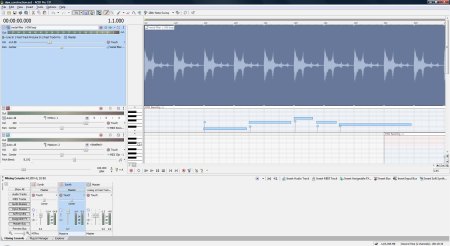

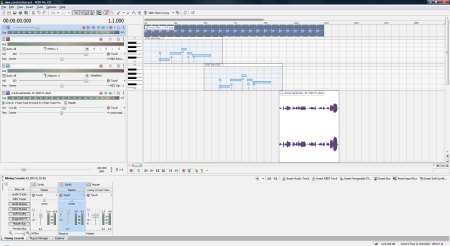

And here is how it looks on the monitor in ACID Pro:

Below the looped audio file you’ll notice five horizontal blue bars. This is a display of MIDI information in a piano roll editor (as opposed to a text editor). The basic blue bar shows the pitch by diagramming its placement on a piano’s keyboard; duration by the length of the bar along the timeline; and how hard the keyboard was pressed or struck by the little vertical wand with a diamond on top. MIDI data can be entered by performance in realtime with any kind of MIDI controller (a piano-type keyboard is the most common but wind controllers (basically a sax mouthpiece), guitar controllers, and percussion controllers are also very common), it can be step-recorded with a controller (a laborious process where you set the length of each note then create it with the controller), or you can even draw in the notes in the MIDI editor.

The mind boggling side of MIDI is that you can play it back with any sound, whether on hardware or software. In this example I merely copied the MIDI clip and placed it on two tracks. The first track is the original sound module, a patch called M’Lady on a software instrument called M-Tron Pro (an emulation of the venerable Mellotron). For the second track I used a purely digital product by Native Instruments called Massive (a patch known as Infatuated).

The last component, and to the poet the most important, is live recording. You can record your voice or any other sound directly into the computer with any of these programs. Or you can record elsewhere with a portable recorder, your phone, or anything else that can capture sound and then transmit it to a computer, then open up the file within the composition program.

The example I’m providing is a recording of my older daughter at the age of five, in 1996, on a cassette 4-track portable studio just a few months after I began working with audio (this singing and babbling goes on for half an hour and only came to an end because the tape came to an end—unfortunately she’s become a rather shy young woman).

This is a screen shot of ACID Pro showing the looped sample, two copies of a MIDI clip, and a fragment of stereo audio (my daughter singing).

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/daw-construction/s-sLH2P

I’ll conclude with one of my compositions, Winter Flowers. With this piece I used a variation of sampling and looping not discussed above. First I’ll let you hear the original field recording of “snow pellets”, little hard balls of snow not quite solid enough to be considered hail. This was then looped in a processing program from Native Instruments (unfortunately long discontinued) called Spektral Delay, a mixture of delays and EQ filters with a visual controller (you can draw how the filters work). I did this several times over, each time with different settings, then compiled them randomly in ACID. To which I added voice and a couple MIDI instruments. The whole thing is very simple.