The music the adults would listen to when I was a kid, in the 1960s, always had the band at the far end of a very large room, barely audible, and the vocalist practically sitting in your lap. This is the pop mix and it’s still in use today, though part of the rhythm section might be turned up enough for you to always feel the thump in your rump (or wherever it hits you and makes you want to dance).

I loved hearing a rock mix, really coming into its own around 1970 when I was starting to collect records, where the singer is just another member of the band.

Just compare Andy Williams’ recording of Moon River with Black Sabbath’s Paranoid, you’ll immediately hear what I’m talking about. If you were to have these songs as background in a crowded room, such as a restaurant, you’d only hear Williams’ voice. Black Sabbath…unless it was played loudly enough to be annoying you might not hear at all. It would just be a garbled mess.

How to mix music and poetry has been an ongoing discussion/debate/argument—depending on how much investment someone has in the outcome and how threatened they feel by criticism—I’ve been having with poets, musicians, and DJs on soundcloud.com, as well as with friends and family.

As I’ve stated, I like the rock mix. I like having the vocal down in the mix not lording it over the other sounds. But I’ve come to the other side, the pop side, with regard to poetry and music. I think I may be consorting with the devil. I’m almost certainly betraying Art (that stuff with that capital A).

Most of my life I’ve created in response to some inarticulate need, some bizarre drive to put things on paper or canvas, to noodle around with images and then words and most recently to do unnatural things to sound. I have rarely made things to please others or to communicate with them. I’d say it’s more how I think, or how I document stages of a thought, so I’d only be trying to communicate with myself. I certainly haven’t done it for money.

But in the past few years, since the spring of 2011, I’ve been posting my recordings on soundcloud.com and other human beings have been interested enough and gracious enough to listen to what I’ve been doing. I think I owe them a little consideration, even if I’m still only trying to communicate with myself.

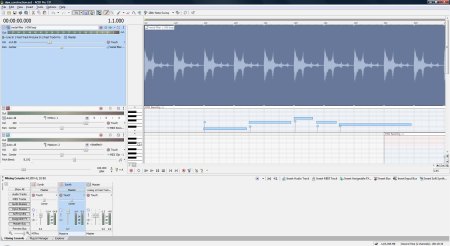

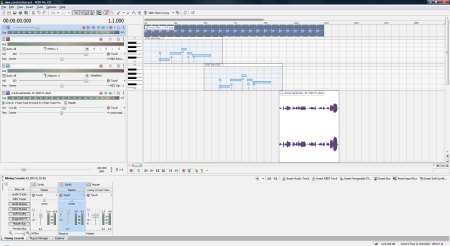

I’ve started to develop my recording and mixing technique in a more sociable direction (not necessarily improving it): primarily, I’ve been using a lot more compression and EQ.

When you speak, the first phonemes, as well as the first words, have more wind behind them, more energy, and will sound much louder than the rest of the sentence. Your first word or two will be loud and clear and possibly overloading the microphone and circuits whereas the end of the sentence will trail off into silence. This varies from person to person depending on their reading/speaking technique, how well they preserve their air supply and how often they pause for breath, as well as how full of wind they are (I’m not going to play with the windiness of any particular poet, myself included). I’m not very physical and I tend to be a mumbler, so when I record myself I drift off into nothingness more often than not. My technique makes it hard for people to hear what I’ve said.

The easiest way of dealing with this is to use compression. As the word implies, compression squeezes things, in this case sound. Your loudest sounds will be squashed so they no longer jump out compared to the other sounds. It gives you headroom, which means that you can turn up the volume of the whole sentence, before you overload and distort your equipment and digits. (This is what they do in radio and TV, especially in advertising, to make things seem louder.) A lot of compression makes everything sound like crap, there’s no longer any dynamic range. Also, it brings up the noise floor: as soon as you have more headroom to raise the overall volume you also raise the volume of the noise, such as circuit noise, tape hiss, ambient noise, computer fans, et cetera (to some extent this can be dealt with by using noise reduction software, but often only in the spaces between the words, depending on the quality of your software and how much and what type of noise).

Because all of the vocal is now louder from compression but without the spikes at the beginning of words, I can make my voice sound louder than the surrounding sounds without overloading the mix. It’ll be easier to hear what I say. The sentences will not trail off the way they did in the original recording.

The other thing I’ve started doing is to tweak the EQ in the mix. What this means is to accentuate or diminish different frequencies to make various sounds or my voice stand out against the others. I’m not going to dwell on this. A quick and rough example should be enough.

Let’s say your voice is not real high, not real low. It probably competes for sonic space with most stringed instruments and parts of a drum kit, such as the snare and cymbals. (I rarely use conventional instruments or samples of them but more than likely you do. Either way, whether using a guitar or a washing machine, the premise is the same.) I will lower the volume on my voice below, say, 500 Hz, or 300, because not much of the articulation is at the low end. That’s where the vowels are. I’ll save that range for other sound sources, let them have their say. But I will bump the EQ a little around 1000 Hz (or 1 kHz) because that’s the area that speech is most legible. That’s where you’re most likely to recognize individual words. It’s the range of articulation. Along with that boost to my voice, I’ll tone down some of the other sounds (for instance, I might notch the guitar part a little around the same frequency range, at least while I’m speaking).

Exactly how much EQ and compression are not just a matter of taste but reflect the kind of instrumentation you’re using and how much you want your words to be heard. If you’re doing just voice or voice with a very quiet and subtle background you might not want to tweak it much, or not at all if you’re a purist. If you’ve got a lot going on, perhaps going for some version of a “wall of sound”, you’ll probably want to make some major changes to the levels.

Enough said about the technology. I want to say more about the history of how I came to more of a pop mix and what the debate is about.

When I started posting my recordings I received comments from listeners who couldn’t hear what I was saying. I’m calling what I write poetry and the idea is that the word is god, so, yeah, they should be able to hear the word. Some of these people were native speakers of English, so this means that they simply can’t hear what I’m saying. Others were only somewhat acquainted with English: first, to accommodate them I started posting the text on the song page; then, to make it even easier, I started posting the text as a comment on the track itself (so at least with the old soundcloud interface they could read it while listening, without having to leave the page they were on).

So far this has done nothing to change the esthetic object. It’s put me out a little, time wise, but the recording remains the same.

But it was still stressful for the listener. That’s when I started digging into my recordings and altering the levels, both in the mix (changing the compression and EQ as well as volume of one track against another) and in the mastering stage, where I can shape the overall sound. This did change the esthetic object. This pushed me from my beloved rock mix to the dread pop mix. (Okay. Art people aren’t supposed to like anything pop, unless it’s an ironically cynical spoofing of pop. Despite how weird and unfriendly my recordings are, I’m actually a pretty mainstream kind of guy. I am not pure. I am most definitely not high art. And, ultimately, I have no pedigree or credentials. Let’s just say I’m a poseur. So, really, by using a more pop sensibility I’m only violating my own taste and not staining my everlasting artistic soul. The soul that I don’t have: I’ve just decided that I’m an artistic golem.)

Sorry for the digression.

Another detail of mixing that I’d forgotten, which brings me out of both the pop and rock esthetic, is that I use little or no reverb. It’s called mixing dry. (I think Lou Reed is one of the few name artists who doesn’t, or didn’t, sweeten his voice with reverb. I will process the hell out of my voice but really don’t want to use reverb. This has nothing to do with Lou Reed’s choices.) I came to this decision because my arrangements are very busy (let’s be honest: cluttered) and even a little reverb made my words that much harder to hear. I came to this conclusion probably ten years before I started posting online. The conclusion to be drawn from that fact is that I couldn’t even understand myself.

The original use of reverb, it’s reason for being once people started recording in a studio rather than a concert hall, was to give the recording a sense of place. It was there to make the band sound like they were in a better room than the one they were actually in. But almost immediately musicians and recording engineers started using reverb as an effect, to sweeten the sound, to give parts of the recording a little something special.

This has now become a source of sonic nightmares, and I don’t mean the creation of recordings that strive to express a nightmare or to capture the dissociation of a nightmare. I mean that reverb is now used to turn music into a sludge of sounds in competing spaces. Anyone who has recently gotten their first effects unit or software with reverb has made garbage (myself most definitely included, even though I was trying to be restrained). The worst of it, though, isn’t the excess of reverb but the conflicting echoes. Almost every instrument, especially electronic synths and samplers, will have its own reverb. So, in the finished recording, you could have it sounding as though each instrument was played in a different room. On top of which the whole composition might be awash in a unifying reverb. I guarantee you will have trouble understanding the poet’s words when reverb has gotten out of control.

Now we get back to the conflicts of opinion and why I often give offense…

It is common for the musicians working with poets, as well as poets themselves, especially those new to the tools of recording, to put the voice low in the mix and to use a lot of reverb. As I’ve now stated, I object to this not for esthetic reasons but for the sake of the listener.

With a song it doesn’t always matter that the listener can’t hear every word that’s sung (in fact, it’s often a kindness). Even when people sing along they aren’t conscious of the words. They couldn’t tell you what the singer just said or what it meant. It’s really just a flow of sounds. Even when the lyricist is superb and the listener should be paying attention that’s rarely the case.

Poetry and any other kind of spoken word demands more of you. When someone talks to you it’s normal to pay attention. You have to listen a little more closely, like it or not. Already, recorded poetry is making demands that a song wouldn’t. Then, if you have the voice so it’s barely audible, buried in the mix and drowning in reverb, you’re forcing the listener to stop whatever it is that they’re doing so they can hear what you’ve got to say. And you’re a poet and think, of course, they should do that. This is poetry. This is serious. Or, you might be thinking that it’s poetry and no one’s going to listen, ever, so who cares if the words are intelligible. Either way, you’re not really taking into account another person’s experience.

Most listeners will turn you off and look for something a little less demanding. Something that fits better in the background of their life. That’s just a fact. No one owes you their attention. No one owes you anything. Good bye, ego.

One of the arguments for more of a rock mix is that most listeners now days have the recording plugged into or around their ears. They aren’t listening on speakers and they’ll hear every word.

Another argument is that a collaboration or remix is not going to be the only version of the poem and that you can link to a clearer recording of the words. Of course my child would be pointing that out to me. I think of listening to music on a dedicated medium such as an LP or CD or tape on a device connected only to other audio devices, such as an amp and speakers. Link? What does that mean?

Yet another point of view, says my partner in a very loud voice, is that a very large percentage of the Earth’s population has better hearing than I.

Of course there’s still the esthetic argument, that it has to work as a whole. I would say the musicians, DJs, and remixers are thinking of how all the pieces fit together, of how they all interact sonically rather than intellectually, and that having the voice stand out would destroy the whole.

And then there’s just plain attitude: I’ll do as I please and the audience can follow me. Which may or may not be a statement of arrogance. Or a matter of integrity. Or insensitivity.

I’m sure there are plenty of other ways of looking at this. Please share your opinions. Dialog is just about all we’ve got.

I don’t really care how you make your recording. I don’t really care how you mix it or whether or not I can hear your words. And if you’re collaborating with me, using my words, I actually don’t care how you do that, either (ideally we both have a go at the material and I can mix it however I please).

What I do want is for you to think about what you’re doing, to have a conscious moment before you give your art and your work to the world. Do you want people to hear your words? Do you want to make it easy for them to listen or do you think they should go out of their way to hear you? Do you want your recording to work as a whole, your voice just another sound? With modern recording technology you can have it all with little or no extra expense. You can very easily make alternate mixes, let your audience download a dozen versions of everything you do. You can trust your audience to make a few decisions of their own.

If you’re a poet, a recording poet, you’ll probably never have a large audience. But maybe a few thousand people would like to hear what you have to say. Think about what their experience is. For most of us there’s an unconscious step in the creative process where you’re more of a conduit or vessel than a human being. But after that it’s a matter of editing the gift, of continuing to shape it, whatever that “it” is, into a public object, a work of art, a shared experience.

Give a little thought and care as to what that object will be.

I’ll part with two examples of my own. The first, Psychedelic Baby of Death, is something I recorded in 1998 or 1999, and is a good example of how hard it can be to hear what I’m saying. My voice is competing with an air compressor (for a nebulizer) and an electric guitar as well as an excess of reverb on all the sound sources. I’ve tried to master it so my voice would be more audible (can’t get rid of all that reverb no matter what I do) but it still requires a lot of effort on the listener’s part.

The other recording is My Soul. This was created in June, 2012, well after I started posting on soundcloud.com, and does a much better job of taking into consideration the listener’s experience.

In case the recordings are not available for streaming, as often seems the case with soundcloud, these are the direct links to the song pages (though of course they might be down as well):

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/psychedelic-baby-of-death

http://soundcloud.com/swampmessiah/my-soul-draft-1

Second post script, October 12, 2013: Several weeks ago I received help from soundcloud.com but could not correctly interpret what I was being told. They suggested I switch to HTML and re-paste the links. I don’t know anything about HTML nor how I would do this, and said so. What they meant, and what someone at WordPress said more clearly, is that I need to use the text editor rather than the visual editor. You can toggle between the two tabs at the top of your editor page. That seems to have fixed the problem.

This is a recurrent problem I have with technical support. We don’t speak the same language and it’s rare that there’s anyone on the support end who understands the subject and can still communicate with those of us who do not. (Does this remind you of math and science teachers?)

I thank people at both soundcloud.com and WordPress.com for their assistance.

Post script, September 8, 2013: In response to David McCooey’s comment regarding his own struggles with the balance of voice to sound, I think the point of the article, though not quite blatantly stated, is that we have no way of predicting the environmental circumstances of the listener. It also, I suppose, pits the creator, who would like to control the final outcome of their creation, against the consumer, who’d like to personalize that precious object to fit their own needs and tastes. Other than wanting to see artists recompensed for their labor, I think we creators need to learn to let go (I know I’m having trouble with this). Once the work has reached the public it is no longer ours. The recipients of our work have now begun to invest it with their own needs and imaginings and emotions, it’s begun to fill their dreams as it once filled ours, it has begun to reshape how they see the world.…I think my digression here is to say that I wish the audience could have the same tools I have—multitrack audio software—to remix the compositions to suit themselves, to bring the vocal down when listening on headphones and to bring it up when listening in the car.